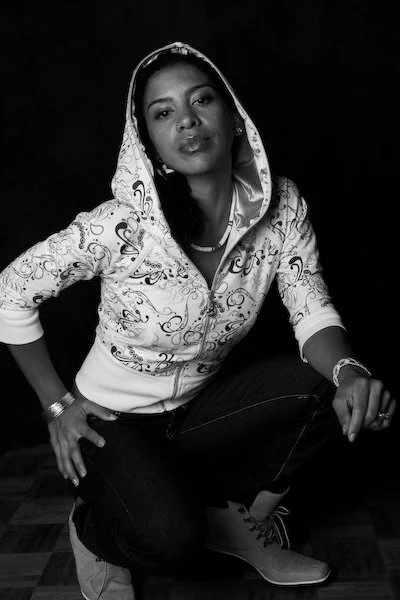

ROKAFELLA on being one of the first women in Hip hop

Photo by Paul G

Ana "Rokafella" Garcia is a NYC native who has represented women in Hip hop dance professionally over the past three decades. She co-founded Full Circle Productions, Inc., NYC's only nonprofit Hip-hop dance theater company, with her husband Kwikstep, generating theater pieces, dance training programs, and NYC-based dance events.

Rokafella directed a documentary highlighting the B-girl lifestyle entitled All The Ladies Say with support from Third World Newsreel and Bronx Council of the Arts. She is hired internationally to judge Break dance competitions and to offer her unique workshops aimed at evolving and preserving its technique and cultural aspects. She has worked within the NYC public school system and various NYC-based community centers, setting up programs that help expose young students to the possibility of a career in dance. In May of 2017, she launched “ShiRoka” -- a t-shirt fashion line with Shiro, a Japanese graffiti artist.

Rokafella has been featured in pivotal Rap music videos, tours, film, fashion shows, and commercials including the Netflix Series The Get Down. She has choreographed for diverse festivals / concerts such as the New York Philharmonic’s Firebird in 2022, the Kennedy Center, Momma's Hip hop Kitchen and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Branching out of her dance lane, she has also recorded original songs / poetry and performed at NJPAC's Alternate Routes in Newark and Lincoln Center Out of Doors.

She received The Joyce Foundation award to collaborate with True Skool in Milwaukee and received the American Dance Festival’s National Dance Teacher Award. Presently, she is an adjunct professor at The New School and Sarah Lawrence College, and a content creator for Bronx Net TV producing her own TV series entitled Kwik2Rok. Rokafella is a multi-faceted Afro Latin Hip hop artist who references Nuyorican culture as her foundation.

Interview by Catherine Tharin

Could you please define Hip hop?

Hip hop is the expression that came about in the late 70s from New York City, predominantly in the Bronx and by predominantly African American and Caribbean Latino males. There were four standout elements - one being the dance, the other being the music, the third (there is no order, I'm just arbitrarily listing), graffiti, and [the fourth] the lyricism of the storytelling. Some people equate and have used the term Hip hop when they're talking about Rap, but Rap is the coming together of the DJ and the lyricist. Hip hop encompasses other elements, including fashion, slang and creativity, and the knowledge of self.

How did you come up with your name, Rokafella?

Down in Times Square in 1991, and Rockefeller Center right where the Atlas is facing the Saint Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue, we would perform for money with established dance groups. I was the only girl. One of the officers who would routinely approach me said, “You know you have to go.” One day, I was just so upset and tired that I said, “You know, you don't even know if I might be, you know, related to the Rockefellers.” Of course, he thought that was funny and we kind of joked about it, but he still removed us. So, from that point on, anytime he would come to remove us he would say, “Alright, Lady Rockefeller, alright, let's go.” It was like a joke.

This name wasn't real but when I started to really get better with my break-dancing moves, I was rocking the fellas. They didn't wanna dance after me. That’s when I decided to take that name on. Rokafella! I was rocking the fellas – “Ohh, that's good, ohh, yeah.” It was those two things that created that moniker and I stayed with it, and I really lived up to it. To be able to have a name with “rock” in it, and Hip hop at the time, to be one of the best.

As a female Hip hop pioneer, in what specific ways were you able to gain acceptance by your male peers?

Women have to work harder to establish themselves as contenders - as equal counterparts to the men. Most parents were trying to protect their daughters and keep them from the streets. Women were looked upon as sex objects. At the beginning if you were going to be a female rapper then you had to be good at battling. You had to write your own songs and know rhymes. You had to be able to move the crowd, be able to impact, control, and dominate the stage. When it first started, it really was about the skills. As dance moved into more mainstream and Hollywood versions, I felt “I can't be showing all parts of my body because my body's on the floor and needs to be protected from scraping and from cuts.”

I had to really prove that I could acquire advanced Breakin skills. Once the men saw me do that in the circle there was instant respect. There was an affirmation of, “Oh, you know that’s a hard one.” As a result, the men would have some sort of solidarity with me like, “You went through the training process. You went through the bruises.” You had to fail before you succeed. There was this mutual respect that I gained, and it was wonderful. It really made me feel like a giant even though I was proving myself every time in the circle.

Where did you find this gutsiness?

It was the atmosphere that I grew up in. The atmosphere of the people before me infused this kind of go get ‘em, go make it yourself. My parents worked so hard to raise three kids and they sacrificed so much and yet I was never going to be able to have what maybe other people have so I had to go out and create it. I created it through dance. At first, my parents didn't want me to dance. They wanted me to try my luck with college and be a doctor or an engineer but [being able to] finance that wasn't available and I knew it early on. So, I decided to focus on the dance.

To learn about the history, the music, the roots, thankfully, the person who became my husband, Kwikstep, ushered me into the knowledge of community members. I could learn and absorb this important information about our community and the roots. Then I was able - instead of just being a dancer - to be on a panel discussion. “Or, hey, I can teach a course, and I can mentor.” When you first set out to dance you don't think of those things, you just wanna move. But, to evolve and remain a pillar in this community you have to bring a depth to it. You must have a very strong presence in this dance form.

There's another woman who I was looking up to when I was first dancing. She's more of a Popper and Locker, and now a standup comic. Her name is Peaches Rodriguez. She's someone that I saw at the clubs and that I saw on the streets. Just watching her do her thing gave me permission to do my thing because there weren't that many of us, and so, there was always that question, “Like, can I do this?” “Am I the only one?” Watching someone who was older and definitely well versed who completely said, “Go ahead, rock it, do it,” inspired people. She's a generation before mine, just a little bit older than 53. She might be 56 but that makes a difference because when she was 13, I was still 10, playing with dolls. When she was 16, and out there, I was still doing my homework.

Rokafella: “The All The Ladies Say documentary clip is exciting because it's this really flashy eye-catching montage of girls doing amazing movements. It gives the viewer a really good understanding of what our lifestyle is because in the documentary we talk about battling our femininity. It's about unpacking what it takes to be this. I tried for it not to [focus] on me because the other dancers were the people that I was looking at.”

You stated, “Being of Latino background, there was a difference between what the males could get away with and what the females had to do." Please explain further.

Men could stay out later, men could be disrespectful, men could be aggressive. Whereas women had this weird pressure to always be good and look nice. Men don't need makeup or high heels or a push up bras! They can be promiscuous. We can't. That's what the standard is. You do what you want but if you're gonna do what you want you have to be able to bear the brunt of the pushback. You really must be an independent thinker and have thick skin to be in this street game or to be in entertainment. There's a double standard in the world.

We are working towards removing the antiquated ways of boxing in women and reducing them and looting a woman's potential. The B-girls who exist now, and of course Missy Elliott who's an MC and rapper, challenge those notions. Missy Elliot didn't have the straight hair and her rhymes were raunchy and political. She was fun and could sing, too. She could produce. There’s Jazzy Joyce and Spinderella of Salt-N-Pepa, both Hip hop DJs, and so many more forward-thinking women who are ambassadors for the culture. They’re not as publicized and promoted as they should be.

We, myself included, have to self-produce. We must create our team and make the projects and programs happen. We have to fund them. Build relationships and wear many hats so that we can do what we came to do. Thankfully, Hip hop gives us some free reign and I mean the culture. I've grown because of Hip hop, because of my activism, because of strength and street smarts. I can step into any of these realms and know how to navigate, negotiate my price, state my conditions and my terms. Yeah, not always easy but I've been fortunate to come this far.

In what ways did your Puerto Rican heritage directly influence your style of breaking?

I had a particular ear for percussion. As a child there were always weekend celebrations, family celebrations like quinceañeras, weddings, baptisms, and birthdays where my family, neighbors, and church buddies got together at somebody's apartment or our apartment. People would bring instruments and I just love that, and I listened to it, and I watched people. I observed and absorbed. When it was my turn to dance, I felt like I could. I understood it. It was instinctual. I picked up dance, regular dance, before I breakdanced at about 19 or 20. It’s what my family infused in us that helped me with Hip hop and helped me connect with African Americans. They helped me understand James Brown and Motown. There was something connecting me to our drums on the island. I had a synergy with that and if ever people would say, “Oh, you're not Black,” I'm like “You're right, but I'm not white either.” The sound is African, but my Puerto Rican heritage features lyricism in songwriting. In the south there's a call and response and the horns with the singer. So yeah, I was connected and ready to step into Hip hop knowing that I could dance to the beat, like I could ride the beat. If I wanted to write a poem or rhyme or rap, I did it, too.

The most difficult movements to master in Hip hop, initially wanting to look cool, are the social steps, because those are the first steps that everybody did. Before you even threw yourself on the floor you had to be able to stand there and rock to the music, whatever music is playing. That's training. You have to be around people who move, and they can teach you. When it comes to Breakin, those Windmill movements were really difficult. The gateway for the other big power moves is the Windmill.

Kwikstep, my husband, was my first break dance teacher, and he started me off with a Backspin which is one of the first ever power moves that leads into the windmill, that leads to Headspins and Tracks and other moves. The flare comes from gymnastics and handstands for the 1990s and flips are acrobatic.

As you mention, your husband, Kwikstep, was your mentor. Could you please describe how he worked with you and the ways in which you worked together?

We had a boyfriend mentor relationship because I met him in ’91 but we didn’t become boyfriend girlfriend until like ’94. We both had this idea of how we will save Hip hop. We both had this activist vein even though we were partying and hanging out. “What is happening here?” Things that are good are being eliminated. There wasn't that much dance going on anymore with the Gangsta rap. Those pressing plants for the records were being shut. The DJ's weren't scratching because the record labels didn't want that. They wanted just a digital audio tape where you just press play and that's it. The rapper is the one getting paid, so we were noticing things like that. We were noticing that Breakin was gone. Michael Jackson kept Poppin alive single handedly. By Poppin I mean like the more robotic type of movements.

When you date you talk a lot. We had these similar observations, and we were like, “What are we gonna do?” Kwikstep was like, “Well, I'm gonna make sure that we keep the four elements together.” I was like, “If you do that then you got to have women.” We were kind dreaming of a future that wouldn't be so diluted. So, we created Full Circle Productions. We were boyfriend and girlfriend and became business partners. It was a relationship that really evolved and strengthened. We got married in 2006. It helped us to grow up and now it's been about 27 years we've had this dance company. Over thirty years together – since 1994. Through great fortune, people connected us to venues or festivals or grant application. People have been generous to share resources with us once people see what it is that we can do and what we've been doing. We’ve helped New York City remain the Hip hop birthplace that continues to nourish the future of Hip hop and not just the commercial aspect of it.

From a recent Works & Process performance at the Guggenheim Museum

In your heyday, you danced with many crews. What did each bring out in you?

The very first crew I was a part of helped me gain experience. It was part of the Breeze Theme/Transformers like the movie, Hello. I still wasn't a bona fide B-girl when I was down with them. They presented performances on the street, as well as indoor shows. Ghetto Original Productions Company was the first company to bring a Hip hop theater production to off Broadway (because Hamilton wasn't the first Hip hop theater production). It was 1992, and Performance Space 122 (PS122) was located on East 9th Street in NYC, turned into Jam on the Groove in 1996. That's real Hip hop history that nobody talks about.

Mark Russell of PS122 booked Full Circle at the New Victory Theater in NYC for three weeks. This really helped me gain stage presence and storytelling and grow go into being a concert dancer that was doing Locking and Poppin in these old school styles. When Kwikstep and I created Full Circle Productions that's when I start to learn to use more of my administrative talents. So, I'm growing. Kwikstep belonged a long time ago to a crew in Brooklyn called Fresh Kids. They adopted me even though I’m from the Bronx. That helped me to expand out of the borough of the Bronx. Now I'm being renowned for my moves in Brooklyn.

I've set up the dance programs in Washington Heights and the Lower East Side. I feel like each year I've managed to share my platform with younger dancers.

I do want to reach a goal where I set up a space in New York City for regular programming whether it's educational dance workshops, dance history sessions or career workshops for people who want to run their own business or how to teach. Kwikstep and I will gather a team of people of different generations to steer this kind of a space. Hip hop was born here, and it should have a headquarters here.

I'm teaching my first semester at Sarah Lawrence College. I've been offering a dance course at the New School since 2015, which introduces students to the culture of Hip hop through its original dance styles and the roots of Hip hop. Since the injuries take longer to heal, I'm a little more apprehensive of attempting a move and so that that kind of hinders me as a coach because I can't demonstrate but for now, I'm still training young dancers. Maybe I’ll produce more music. I haven't really written any songs since 2019.

Could you please comment on aging as a Hip hop dancer?

I can't do all the steps I did when I was 18. Luckily, there are some video clips of me doing some very death-defying movements for a woman. I don't know if you saw some of the Olympics. Those were amazing women dancing. The bar has definitely been lifted but I was one of the first. I have that reputation from the past of being that kind of dancer and that kind of woman in Hip hop. When I'm on stage I have a lot to offer still. I'm 53 so I'm at a different phase but I'm still commanding that respect for how I dress and how I speak and how I negotiate things. I’m aging in dance. I'm aging in Hip hop and yeah, I'm very aware of how people look at me or want to market me. Things have definitely changed and become more cosmetic. Hip hop is similar to gymnastics - that age range is young because [the forms are] so tough.

You are a judge for many Hip hop competitions. In general, what do you look for in a promising competitor?

I like that a dancer can have musicality and dance up top which is the introduction to what the dancer is going to present. It's called Top Rock. I need musicality and some unique flare with transitions that are smoothed from the top to the floor footwork which are the shuffles. Also, the footwork patterns that we do and the power moves, and spins. There's an elite level – those with the skill where there’s no falling, no crashing, and if you do fall how do you clean it up? I look for swag, you know, the posturing. There has to be some aggressive ownership of dominating the floor. A little bit of ego needs to show up - that fire. I just love it when I can feel fearlessness and confidence because they've trained hard enough and there's no questions or doubts. There's no hesitation when they're dancing. That's what I look for.

I really am disappointed when people sign up and they’re just there for a competition and their low level of skills is evident. I'm so disappointed. There should be somebody saying, “They're not ready.” Dancers should say, “Ohh we should wait” but I feel like in this society now dancers just get chosen for trying.

Hip hop has always championed excellence, particularly Black excellence which always had to fly in the face of racism. If this starts with a certain message that says, “We're amazing, check us out, show us love.” That message still must be in the presentation - what you are wearing, how you show up to honor the generation before you that put this together, that laid down the blueprint. That's what I'm looking for.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.

CATHERINE THARIN choreographs, curates, teaches, and writes. She danced in the Erick Hawkins Dance Company in the 1980s and '90s, was the Dance and Performance Curator at 92NY, NYC, for 15 years, and was a senior adjunct professor at Iona College, New Rochelle, NY, for 20 years. She writes dance reviews for The Dance Enthusiast and The Boston Globe, articles about dance for Side of Culture, and reports on dance for WAMC/Northeast Public Radio. She curated a 2024 dance season at Stissing Center, Pine Plains, NY. She continues to teach the Hawkins philosophy, technique, and repertory as an artist-in-residence. Her latest dance is a collaboration with jazz composer Joel Forrester and filmmaker Lora Robertson. Says Fjord Magazine of her work presented in November 2023: "gentle and precise movement contained to a small range, a good deal of floor work...cast a net of whimsical translucent sheen over it all. The evening was consistently charming, well-crafted and paced."